Enhancing accessibility of maps

Table of Contents

Introduction

- Map reading and map creation play very important roles in many fields of study such as Geography, History, and Meteorology. Maps can present a wide range of information. There are diverse types of maps as well.

- In this section, there are some generic and useful resources of accessible maps. These resources are not exhaustive or definitive. They may or may not cover the required technical detail for discipline-specific maps, such as coding and programming. It would be out of the scope of this Toolkit to go through maps for different fields in detail.

Overview of suggested practices

- Multi-modal presentation

-

- Explore multi-modal presentation of map information.

- Provide alternative text (“Alt Text”) for maps.

- Legend and annotation

-

- Use multiple visual cues to present information.

- Use appropriate font and punctuation for legend and annotation.

- Be mindful of the use of symbols.

- Use of colour

-

- Ensure sufficient colour contrast.

- Accessibility check

-

- Test accessibility of the map reader navigation.

Multi-modal presentation

1. Explore multi-modal presentation of map information.

- Maps are often highly visual in nature so map reading would often be potentially inaccessible to many people with visual impairment. It is important to also consider the diverse access needs and potential barriers of map reading to other users. Collect users’ opinions and conduct user testing on the accessibility of map reading and map creation whenever it is possible.

- Overview of common map accessibility errors and the impact on users with a disability. AccessibilityOz.

- Accessible Maps. Wiki page authors: Klaus Miesenberger, Reinhard Koutny, University of Linz, Institute Integriert Studieren.

- Explore the availability, applicability, and possibility, of developing multi-modal presentation of map information. For example, visual-based paper maps may incorporate tactile and/or acoustic presentation of the information to cater for the access needs of a wider range of users.

- Techniques to make Visual Maps Accessible to People with Visual Disabilities. Wiki page authors: Klaus Miesenberger, Reinhard Koutny, University of Linz, Institute Integriert Studieren.

2. Provide alternative text (“Alt Text”) for maps.

- Provide alternative text (“Alt Text”) for maps to make it more accessible to assistive technologies.

- Alternative text (“Alt Text”) concisely describes the content and the purposes of the maps in brief phrases or 1-2 sentences.

- Alt text enables screen reader users to understand maps. When screen readers recognize the graphical content with Alt Text, screen readers will read “Image” or “Graphic” followed by reading the associated Alt Text.

- Sighted users generally do not see the Alt Text. However, when images do not load successfully and/or the browsers block images by default, Alt Text of that image may display to let users know what the image is about. Sighted users would also see the Alt Text under this situation even if they are not using assistive technologies.

- Do not write detailed and lengthy description of complex content of the maps as Alt Text. Consider providing the lengthy description separately as text description. It helps every user understand complex content of the maps, not only screen reader users.

- In general, no need to begin the Alt Text with phrases such as “Picture of…” or “Image of…”

- When screen readers recognize an image with Alt Text, screen readers will read “Image” or “Graphic” followed by reading the associated Alt Text.

- Include the informative text embedded within the graphical content in the Alt Text.

- Be aware that hyperlinks in the Alt Text cannot be activated or presented by link text.

- Use punctuation such as periods to end the Alt Text. Otherwise, screen readers may mix up the Alt Text and the main body text that follows. It may confuse the users.

- For any acronym in the Alt Text and/or image description to be read aloud letter-by-letter (such as “I” – “D” – “E” – “A”) instead of as a word (such as “IDEA”), the letters in the acronym should be spaced out (such as “I D E A”) to enable assistive technologies such as screen readers to read it letter-by-letter.

- Multiple graphical content sharing the same message can be grouped. Provide an overall Alt Text for this entire grouped graphical content.

- Graphical content that are purely for visual decorative purposes, for formatting purposes (such as stylistic borders), repetitively used, or do not provide meaningful information generally do not require Alt Text.

- Refer to the following guidelines to know about more examples of writing informative text description of maps content.

- Long descriptions for maps. AccessibilityOz.

- Image Description Guidelines (Art, Chemistry, Diagrams, Flow Charts, Formatting & Layout, Graphs, Maps, Mathematics, Page Layout, Tables, Text-only images). The DIAGRAM Center.

- Effective Practices for Description of Science Content within Digital Talking Books. The WGBH National Center for Accessible Media.

It covers guidelines for writing image descriptions for bar chart, line graph, Venn diagram, scatter plot, table, pie chart, flow chart, standard diagrams or illustrations, and complex diagrams or illustrations. - NWEA Image Description Guidelines for Assessments (PDF; 5.6 MB). The Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family National Center for Accessible Media at WGBH (NCAM).

It cover discussion about challenges and guidelines for writing image descriptions for a variety of images, charts, and graphics targeted to the assessment of reading, language usage, science, and mathematics. - Excerpts from the NBA Tape Recording Manual, Third Edition. National Braille Association.

Instruction and examples of describing complex images.

- Other references of writing alt text or image description for images:

- Flowcharts & Concept Maps. Pennsylvania State University.

- Documentation Screen Captures. Pennsylvania State University.

- Best Practices for Accessible Images. California State University, Northridge.

Legend and annotation

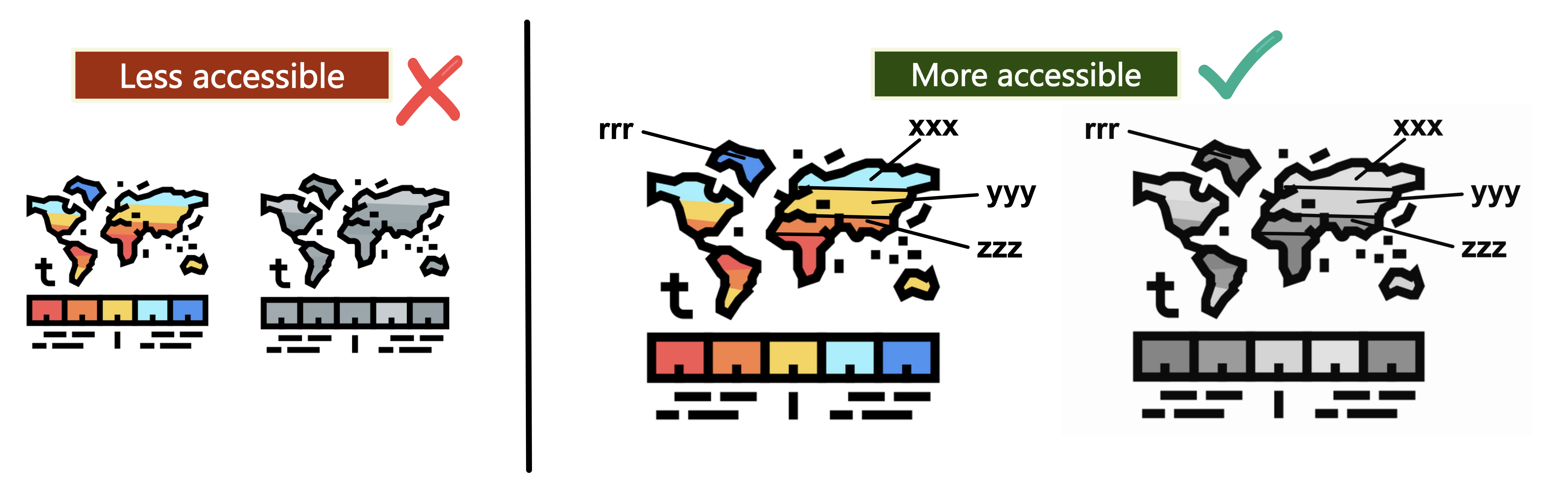

3. Use multiple visual cues to present information.

- People with colour blindness, with low contrast sensitivity or some visual impairment, may have difficulty distinguishing between certain colours. Therefore, using only coloured visual cues to convey important information could hinder understanding of the maps.

- Use multiple visual cues to present information to enhance accessibility to wider range of users, especially graphics, tables, and charts, such as colour, pattern fill, line style (e.g., solid, or dotted lines), data labels, text description, and/or legend.

- Put the text labels and annotations near or directly on the corresponding map section to enable readers to understand the map clearly. Do not put all the text labels only in the legend.

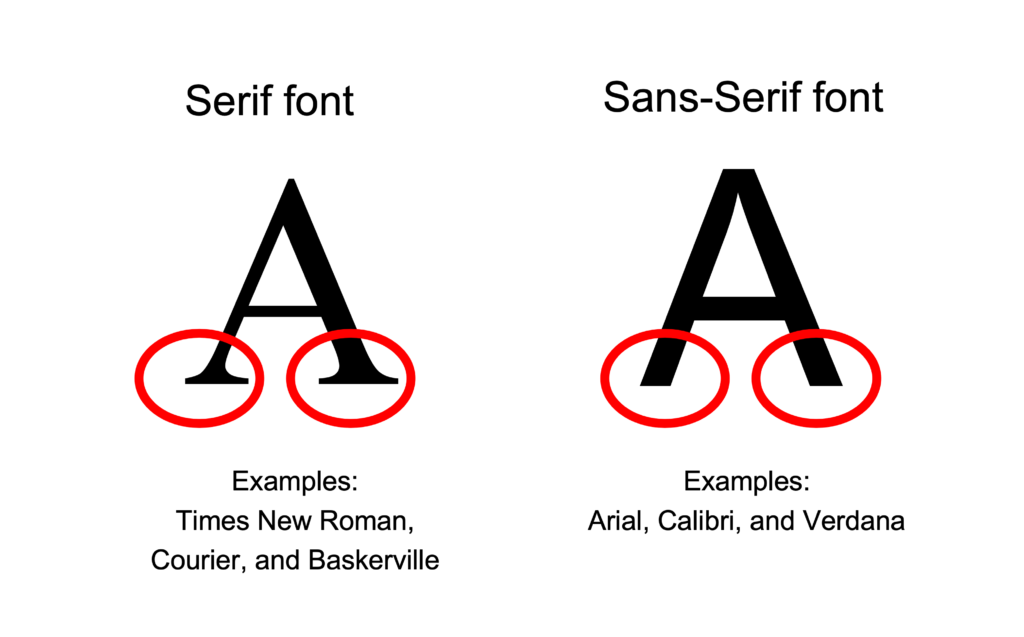

4. Use appropriate font and punctuation for legend and annotation.

- Sans-Serif fonts, such as Arial, Calibri, and Verdana, are generally preferred to Serif fonts.

- Sans-Serif font do not have decorative lines at the edge. An example is Arial.

- Serif fonts have small lines at the edge that may hamper readability. Some users, especially people with dyslexia, might find it hard to read decorative fonts and those whose letters are close to one another. An example is Garamond.

- Avoid light fonts.

- Use appropriate font size.

- Use appropriate punctuation. Be aware of punctuation that visually looks similar but symbolize different meanings. Otherwise, it would make users assistive technologies such as screen readers difficult to understand the content.

- For example, be aware of the differences between the marks of ” inches, ‘ feet, ’ apostrophe, “ ” quotation marks. Use the marks of “smart quotes” as the quotation marks. Do not use the marks of “straight quotes” as the quotation marks.

- Avoid using all caps or small caps. It is difficult for most people to read.

- Text with all caps or small caps may show no differences in the shapes of texts, and all the texts may visually appear a single “rectangle”. It would particularly create barriers to some people with visual impairment and some people with reading disabilities.

5. Be mindful of the use of symbols.

- Different assistive technologies may recognize symbols differently.

- For example, some screen readers may recognize and/or read out the “ – ” symbol differently. Some screen readers may not understand whether the “ – ” symbol represents the meaning or function of “en dash”, “em dash”, “negative”, “minus”, or “hyphen”.

- Consider spelling out the intended meaning or function of the symbol in text to avoid confusion. For example, write “25% to 50%” instead of “25% – 50%”. Make a remark within the map, legend, annotation, and/or supplementary information section to indicate the intended meaning or function of the symbols if needed.

Use of colours

6. Ensure sufficient colour contrast.

- Make sure to check colour contrast for the maps, legend, and annotation. Content with sufficient colour contrast is easier for everyone to read. Content without sufficient colour contrast would be inaccessible to some users, particularly:

- People who are colour blind;

- People with visual impairment;

- People viewing the maps through monitors in bright sunlight or glare;

- People viewing the maps through a projector display in a well-lit venue.

- Make use of software applications to check colour contrast. There is a number of colour contrast checkers that are free-of-charge.

- Colour contrast is checked against the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) using these checkers. Enter the colours of the background and foreground (e.g., text), respectively. These checkers generally allow multiple methods of entering colours, such as the colour picker tool, RGB colour codes, or hex colour codes. The colour picker is particularly useful to users who are unfamiliar with colour codes. Then, the checkers will tell whether this colour combination would fulfil or fail the colour contrast requirements based on the WCAG Guidelines. If it fails, then it might suggest that we need to consider changing the colour of either the background or the foreground colours, or both. Otherwise, this colour combination might not be visually accessible to some readers. After we change the colours, re-do the check, until you get a combination that fulfils the accessibility requirement.

- Examples of colour contrast checkers that are free-of-charge:

- WebAIM Contrast Checker: An online checker.

- WebAIM Link Contrast Checker: An online checker. It helps check the colour contrast between the link text, the surrounding body text, and the background colour.

- Colour Contrast Analyser (CCA) from TPGi: It needs to be downloaded onto your computer, available for both Windows and Mac. It also provides a Color Blindness Simulator.

- Adobe Colour Contrast Analyzer: An online checker. You may input the text colour and background colour values or upload a screenshot of your project to pick the colours you want to check for contrast. It will also recommend colours that would give better contrast. In the Accessibility Tools tab of the Adobe Colour Contrast Analyzer, apart from general colour contrast checker, you can choose the Colour Blind Safe Checker to check whether the colour theme or palette would be accessible for people with colour blindness.

- Check whether the maps, legend, and annotation are readable and properly displayed in grayscale. Modify the colours and/or apply alternative solutions (such as adding text annotations) if any parts of the maps, legend, and annotation do not present the intended meanings under colour filters. It is useful and important practice because many students would print out course materials as handouts in black-and-white.

- Examples of colour filters for checking grayscale display:

- Windows Built-in colour filters: Go to Start > Settings > Ease of Access > Colour Filters. Switch on the toggle for colour filters.

- Mac Built-in colour filter: Go to Apple menu > System Preferences > Accessibility > Display > Select Colour Filters > Select Enable Colour Filters > Select Grayscale in the dropdown menu. Then the grayscale filter will be applied to the entire screen.

- Try selecting the other colour filters in the dropdown menu to view the maps, legend, and annotation in simulated colour blindness situations. Fix any parts that do not present the intended meanings under colour filters.

- Examples of colour filters for checking grayscale display:

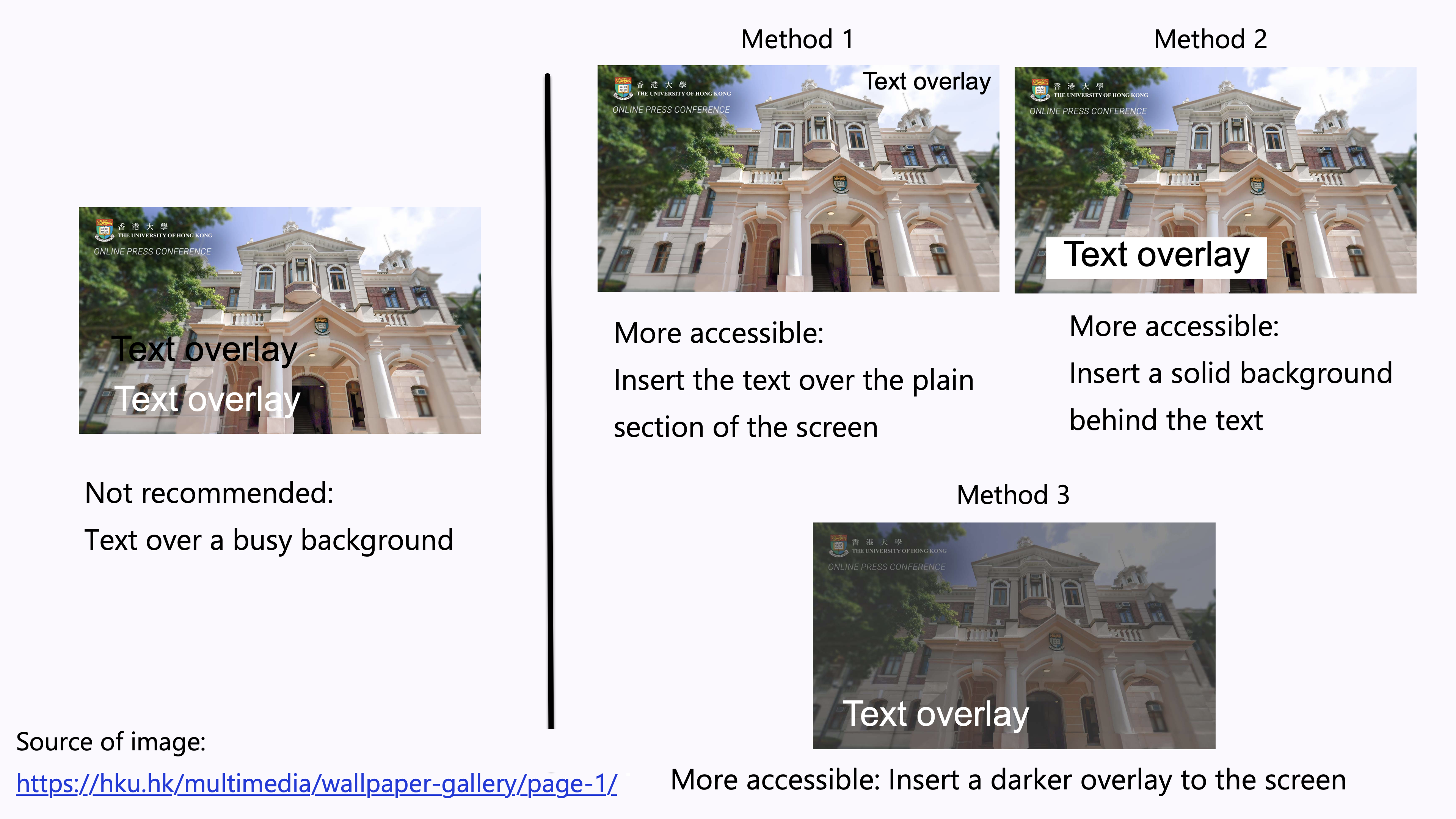

- Do not use “colour-on-colour” background and text, such as light blue text on dark blue background.

- Ensure sufficient colour contrast between the link text and its surrounding body text. Ensure the colours of the not-yet-visited hyperlinks and visited hyperlinks show sufficient contrast against the background colours, respectively.

- An example of online checker for link texts: WebAIM Link Contrast Checker.

- Examples of increasing the accessibility of the text overlay:

- Method 1: Insert the text over the plain section of the photo. Ensure sufficient colour contrast between that section and the text.

- Method 2: Insert a solid background behind the text. Ensure sufficient colour contrast between the solid background and the text.

- Method 3: Insert a darker overlay to the image to increase the colour contrast between the background and the text.

Accessibility check

7. Test accessibility of the map reader navigation.

- Try inviting people with disabilities through university’s student affairs unit, NGOs referral, open recruitment, or personal invitation, to test the map reader accessibility, share their user experience and possible alternative solutions to any potential inaccessibility issues.

- Try navigating the map reader using only a keyboard (e.g., the TAB key only) instead of a mouse. It helps test the keyboard control accessibility.

- Try different screen readers to test whether the equations, symbols, and characters are supported. Examples of screen readers are:

- Narrator in Windows, built-in voiceover function in Windows;

- VoiceOver on Mac, built-in voiceover function in Mac;

- NVDA, screen reader that can be downloaded free of charge by everyone; available for computers running Microsoft Windows 7 SP1 and later;

- NVDA add-on developed by the Hong Kong Blind Union with a Chinese speech engine.

- Test for any problems with the content when the map is magnified to around 200%.

References

- Accessibility in ArcGIS Pro.

- Accessibility topics in ArcGIS Blog. Esri.

- Esri Accessibility articles and blogs, videos and presentations.

- Making Maps Accessible to the Blind and Partially Sighted. esri ArcNews.

- Map Accessibility: Map Design, Static Maps, and Interactive Web Maps. Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Esri ArcMap 10.X and Adobe Accessible Color Swatch Styles. Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Tips for Accessible Map Design (e.g., Colour, fonts, labels, and symbology). Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Map Design Guide Best Practices Ensuring Accessibility/Usability. Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Map Accessibility Presentation (PDF, 6.2 MB). Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Accessibility Guide for Static Digital Maps (January 2019) (PDF, 2.2 MB). Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Accessibility Guide for Interactive Web Maps (December 2021) (PDF, 2.8 MB). Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Accessibility Guide for Interactive Web Map Tools (December 2021) (PDF, 717 KB). Minnesota IT Services (MNIT).

- Improved accessibility in the Maps JavaScript API. Google Maps Platform.

- Interactive Maps. AccessibilityOz.

- Maps. Pennsylvania State University.

- Accessible Maps. Wiki page authors: Klaus Miesenberger, Reinhard Koutny, University of Linz, Institute Integriert Studieren.

- Cole, H. (2021). Tactile cartography in the digital age: A review and research agenda. Progress in Human Geography, 45(4), 834-854. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132521995877

- Wabiński, J., Mościcka, A., & Touya, G. (2022). Guidelines for Standardizing the Design of Tactile Maps: A Review of Research and Best Practice. The Cartographic Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/00087041.2022.2097760